| |

An unknown civilization just 150 years ago, teams of archaeologists and scholars from around the world spearheaded projects exploring, excavating and restoring these ancient Maya cities. Fueling their passion are amazing new discoveries and previously unknown settlements that modern technology is helping to reveal.

In Discovering the Maya-Part 1, we admired and chastised the findings and fumblings of early explorers as they pondered immense and mysterious structures in the middle of the rainforest. They struggled in their journeys by land, water and air; yet even today reaching them is an adventure in itself. And what marvels and mysteries are to be found upon arrival. Come along with me as I reveal continuing and remarkable findings.

THE WORK AND DISCOVERIES ARE NEVER DONE

When a team sets its ambitions and energies on a vegetation-blanketed mound or 1,500-year-old building in disrepair, the results can be swift and mind-boggling.

Visiting Yaxhá in 2005, Guatemala’s third-largest site, I noticed a huge mound near the entrance. When I returned two years later, I was stunned to see what the German team had revealed beneath that massive knoll.

Tikal’s second tallest structure, the 187-foot Temple V, underwent an extensive restoration project costing nearly $1 million in U.S. dollars. Comparing visits in 2002 and 2005, it was easy to appreciate what they had accomplished including the construction of a greatly improved staircase to the top. |

Situated in the middle of 222-square-mile Tikal National Park and designated both a UNESCO Cultural and Natural World Heritage Site, Tikal was a major powerhouse in the Maya world. When it was rediscovered in the mid-1800s, photography and site exploration occurred sporadically until the early1900s. When the Guatemalan military cleared an airstrip in 1951, major excavation work became feasible. The University of Pennsylvania worked the site from 1956-1969, and a decade later, 18 archaeologists and 500 workers spent seven years exploring the Lost World complex, possibly the oldest section of the city and its original core.

The Guatemalan government is sponsoring the long-term Proyecto Nacional Tikal whose ongoing work continues to unearth structures and comprehend the lives and politics of a city occupied for nearly two millennia. Thus far, more than 3,000 buildings have been at least partially explored, and three times that number may still lie beneath them.

Work in the Plaza of the Seven Temples included excavating and restoring the central and

largest

structure in a series of seven small, closely-spaced temples, and excavating walls in a nearby palace. |

On the banks of a lake near Tikal, Yaxhá sat unnoticed until 1904 when Tobert Maler spotted its massive temples from the lake which gave the site its name. Mapping and excavation work didn’t begin for another 65 years, but eventually identified over 500 structures stretching across several square miles. In 1994 the Cultural Triangle Yaxha-Nakum-Naranjo National Park was created, with a dozen archaeologists and hundreds of workers excavating and restoring the site in cooperation with the German KfW Group.

| |

Workers unearth a building in Yaxhá’s North Acropolis, with a nearby excavation tunnel revealing various construction layers, methods and material. Finds include architectural models of the city carved from limestone, evidence of 2,000-year-old urban planning. |

|

|

|

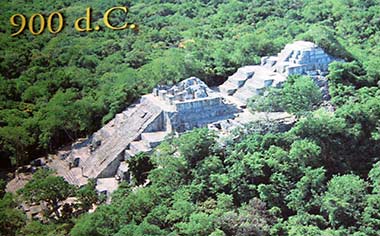

Perhaps Tikal’s biggest rival, Calakmul, is another UNESCO Cultural and Natural World Heritage Site, surrounded by the 70,000-square-mile-plus Calakmul Biosphere Reserve. Discovered while harvesting chicle from the sapodilla tree, local chicleros notified archaeologists of the site in 1931. Nearly 7,000 structures have been identified in the 27-square-mile city, many now excavated and restored. Current work by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) is the most extensive to date and helps to understand shifting alliances among the Maya city-states.

| |

The 180-foot summit of Calakmul’s most massive construction, Structure II - actually, the entire upper half of the building - isn’t even visible from ground level, but the poster of it in the visitor shelter at Becán provides an aerial view. Four or more building phases and an excavation tunnel are visible on the route to the top. |

|

|

|

The year after he discovered Yaxhá, Maler stumbled upon Cancuén, but it took ten years before it was explored and another half-century before a group of Harvard graduate students spent a few days making rough sketches. In 1996, nearly thirty years later and working with the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture, the Cancuén Regional Archaeological Project was launched under Arthur Demarest and a Vanderbilt University team surveying, excavating, and restoring the massive Palace complex.

Over ten years' work revealed the largest Palace complex yet found in the Maya world: 270,000 square feet covering five acres. Excavation pits helped divulge three levels, 12 courtyards and more than 200 rooms, some with ceilings that soared 20 feet high. Workers are restoring a wall of the royal ball court, also contained within the Palace grounds. |

Located on the banks of the Río La Pasión, Cancuén was a major trade hub, making it both prosperous in its day and a prime target for looters. Particularly epidemic in the 1950s, a number of stone monuments held in private collections are currently being tracked down. Thieves are so brazen that when rains exposed a 600-pound stone ballcourt marker in 2001, it hit the black market before authorities were even aware of its existence. Fortunately Guatemalan undercover agents, archaeologists and local villagers worked to retrieve it.

Remnants of a Cancuén stela (a plain or carved stone monument)

sawn into pieces to feed the antiquities black market.

Even the Palace

has three looter’s trenches cut deep into the stonework.

Community Development

is part of the Cancuén Project, and works with local Maya to provide

various

service and tourism-related jobs to help prevent looting and destruction at the site,

and has provided income, schools, medical supplies, and a water system.

An amazing moment occurred in 1938 when a mahogany logger encountered the largest Maya site yet found in Belize. The heart of Caracol covers 15 square miles, but the city and its 36,000-plus structures stretch across nearly five times that much area. Beginning in 1985, the Caracol Archaeological Project has used traditional ground methods to investigate about nine square miles, examined more than 3,000 constructions, located nearly 100 tombs, and uncovered two dozen miles of causeways.

In 2009 Caracol became the first Maya region to have airborne laser swath mapping (ALSM) conducted. After covering almost 80 square miles, many more buildings, roads and agricultural features were found.

The front of Structure B5 is flanked by two masks of Tlaloc, the Central Mexican rain god (sometimes called the Water Lily Serpent masks). Both building and masks were buried beneath a later construction. To preserve many of Caracol’s fragile façades, an exact copy was carved from clay, covered with fiberglass, painted to replicate the original, then placed over the ancient stucco surface to protect it. |

Copán’s mysteries have intrigued scholars ever since a Spanish explorer happened upon it nearly 450 years ago, and Harvard’s Peabody Museum began excavations in the 1880s. A century later, the Honduran Institute of Anthropology and History (IHAH) launched the Copán Archaeological Project, and from 1989-2003, the University of Pennsylvania conducted excavations of the Acropolis.

| |

Honduras, Copan Altar Q side 1 |

|

Copan hieroglyphic stairway and Stela M |

|

Structure 16, Copán’s tallest pyramid and centerpiece of the Acropolis, was a treasure trove of discoveries. Situated immediately in front, Altar Q (above left) is arguably the most important historical document from the site, providing a pictorial "summary" of the city’s 400-year dynastic sequence. The sides of this four-foot square carved stone contain superb reliefs of Copán’s sixteen kings, each seated on a hieroglyph bearing their names. This original is located in the Copán Sculpture Museum and a replica placed in situ.

Ascending Structure 16 is the 63-step Hieroglyphic Stairway (above right), constructed of more than 1,250 stone blocks engraved with some 2,500 glyphs tracing the lineage of Copán’s kings. It took almost a century to reconstruct the Stairway and decipher most of the glyphs, the latter assisted by combining a 3D scan of the glyphs done in 2017-18 with the glass-plate negatives taken by the Peabody Museum team well over a hundred years earlier.

As archaeologists tunneled beneath the pyramid and its stairway, they discovered numerous earlier periods of construction. The Margarita Tomb contained a female occupant accompanied by one of the richest burials ever found, although looters disrupted the field research by stealing valuable material before it could be recorded. The Hunal Tomb, found at least eight construction periods deep and two levels beneath the Margarita Tomb, is believed to be that of Copán’s founder.

An exact full-scale replica of the Rosalila Temple greets visitors entering the Copán Sculpture Museum. Measuring 46 feet tall by 62 feet square, it wears the same vibrant colors as the original.

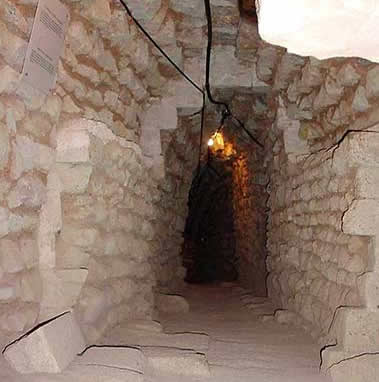

The biggest surprise was finding Structure 26, a.k.a. the Rosalila Temple, in the middle of Structure 16’s long sequence of building and rebuilding. Normally the Maya “terminated” buildings by reducing them to rubble to form the foundation of a new structure. But Rosalila was carefully preserved by covering the entire edifice with plaster before encasing it within the next construction, the only such conserved Maya structure yet found. While touring the excavation tunnels with Ricardo Agurcia, the archaeologist who discovered Rosalila in 1989 while excavating Structure 26, I listened as he described what it was like removing layers of fill to reveal an intact building, its superb carvings and vivid colors staring back at him.

| |

|

|

The Los Jaguares Tunnel runs nearly a half-mile beneath Structure 26,

with glimpses

here and there of other earlier structures

buried inside Structure 16.

|

|

| |

The Rosalila Tunnel, almost 1.5 miles in length, accesses the Rosalila Temple. |

|

|

|

A massive site covering much of the nearly 200 square mile Copán River Valley, a royal residential area is currently being unearthed in a project by the Institute of Archaeology of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (IACASS) and IHAH. Among other findings, their work is helping to understand royal lineages and possible collapse of dynastic rule. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, Copán has a serious looting problem with a tomb having been robbed in the midst of excavation.

Even folks who have never heard of Palenque might recognize Lord Pakal’s sarcophagus lid, frequently ballyhooed as portraying a man operating an otherworldly vehicle. This interpretation would shock the archaeologist who spent four field seasons clearing rubble from stone steps plunging 80 feet down the center of the Temple of Inscriptions, tallest pyramid in Palenque. What he found at the bottom was a sealed triangular door leading to the most extravagant burial outside of Egypt. Unfortunately, the magnificent jade mosaic mask that covered Pakal’s face has been stolen from Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology.

The Temple of Inscriptions was the only structure at Palenque designed and built around a burial chamber. Carved in place, sides of the 15-ton limestone sarcophagus contain images of Pakal’s ancestors, and the 5-ton lid portrays his death and rebirth from the underworld by ascending the Tree of Life. |

The Palenque Project completed a remap of the site in 2000 using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and identified almost 1500 structures. Non-invasive technology is such a change from the 1786 attempt to probe Palenque using crowbars and colossal bonfires. (More Palenque mishaps are described in Discovering the Maya-Part 1) Recent findings continue at this UNESCO World Heritage Site, including Temple 20’s tomb decorated with the first murals found at Palenque, additional noble and royal tombs, and a spring-feed pressurized aqueduct.

TURNING WHAT WE THOUGHT WE KNEW UPSIDE DOWN

El Mirador is so amazing it has been featured in a number of TV series and specials over the past year, and may be the most exhilarating site to access. Located deep in the Mirador Basin, a 1.6 million acre swath of rainforest in northern Guatemala and home to some of the earliest and biggest cities of the ancient Maya, El Mirador has been referred to as the “Cradle of Maya Civilization” and may have been home to as many as 200,000 people.

A thriving city by circa 600 BCE, it had been abandoned and forgotten by the time other Maya cities were reaching their zenith. An 1885 survey of the Basin made note of “grand ruins”. Pilots who flew over the area in the 1930s, rumored to have included Charles Lindbergh, thought it was dotted with volcanoes and would never have believed they were jungle-shrouded pyramids. It wasn’t until 1962 when a Harvard University archaeologist mapped part of the site that El Mirador was officially documented.

The Jaguar Paw Temple held evidence that Maya civilization flourished hundreds of years earlier than previously thought. To protect the stucco carvings flanking the steps, Richard Hansen and a

Boeing engineer designed a protective cover to filter UV light and deflect rain.

Archaeologists from Brigham Young University began excavating in 1979 and it wasn’t long before Richard Hansen, who now directs the Mirador project, found the first stunning revelation from El Mirador. As he excavated The Jaguar Paw Temple, he found pottery shards proving the structure was a half millennium older than originally believed, astonishing the archaeological world.

| |

El Mirador Central Acropolis frieze |

|

Mirador frieze (image courtesy University of Utah) |

|

At the time of my visit to El Mirador, a small portion of the now famous Central Acropolis Frieze had just recently been unearthed. Because its discovery, and as-yet unrealized major significance, had not yet been announced to the archaeological world, we were only allowed into the excavation area (above left) one at a time, with a guide, and without any camera or other recording device. The two 26-foot stucco panels (section of wall above right courtesy of the University of Utah) comprise the oldest known intact Maya wall and depict scenes from the Popol Vuh, the Maya creation story. It was long believed the Popol Vuh had been influenced by Spanish missionaries, but this frieze, dating to 300 BCE -- nearly two millennia before Europeans arrived -- proved it was an untainted belief.

Viewed from a helicopter flying into El Mirador, La Danta towers 230 feet above the jungle floor – the tallest Maya structure discovered to date. And at a volume of 99 million cubic feet, the biggest pyramid in the world. Comprised of three massive platforms, the base covers nearly 45 acres and the second level about four. The third level (above center) was a maze of scaffolding and supports. Weaving through this erector set, one was now faced with a near vertical ascent to the top (above right), aided by ropes near the approach to the summit. It is now accessible by a sturdy wooden stairway, with handrails. Fear Factor muchly reduced. |

Teams from 66 organizations and universities have lent a hand at El Mirador. Since 2003 the Global Heritage Fund has stepped in to help in the site’s protection, which is greatly challenged by looters and poachers and by deforestation from logging and wildfires.

It was the painted murals discovered at Bonampak that turned scholars’ image of a peaceful Maya society upside down. A smaller site revealed by the local Lacandón Indians in 1946, it is famous for the three-room Structure 1, a.k.a. Templo de las Pinturas, whose walls are covered in frescoes of nearly 300 half-to-one-third life-sized figures forming a continuous narrative of courtly life. It was Room 2, known as the “torture” room for the horrendous images of bound and bloody captives, that the true nature of the Maya and their warfare began to be understood. Numerous burials have been unearthed at the site, including the 2010 discovery of a skeleton in Room 2.

Room 1, the Courtly Procession, includes musicians

playing drums and flutes and shaking gourd rattles.

In what, under other situations, would be a Comedy of Errors, Carnegie archeologists from the first expedition doused the murals in kerosene to “bring out their colors.” Then the protective roof constructed to keep the murals dry allowed salts to accumulate on the surface of the murals and form an opaque crust. More kerosene was used to remove the calcite, which weakened the plaster so much that paint and plaster began flaking off. Some of the workers smoked in the rooms. By 1960, Mexican archaeologists took control of Bonampak and began their own restoration of the murals. Rather than kerosene to moisten and clean the paintings, they used water. Unfortunately the water came from a local swamp and organisms from the swamp began to grow on the walls. Fortunately, in the early 1980s, a team of Mexican and international art restorers began a comprehensive cleaning and restoration of the murals.

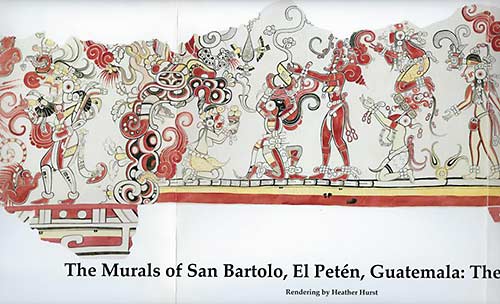

Sometimes looters can help in discoveries. In 2001 William Saturno, Boston University Associate Professor of Archaeology, used a looter’s tunnel to escape the heat while scouting San Bartolo. Using his flashlight to see what he was entering, Saturno discovered the most intricate Maya paintings yet found. Dating to around 100 BCE, many images were deciphered by comparing them with the Popol Vuh, providing a manuscript of Maya mythology and an aid in deciphering their language.

This section of mural from the North Wall is called the Gourd Birth Scene.

William Saturno directs The San Bartolo Mural Project

which is conserving them and trying to protect them from looters.

Thus far, more than 200 looters' tunnels and trenches have been encountered.

ALL MANNER OF ASSAULTS

| |

Takeshi Inomata |

|

Aguateca Stela 7 |

|

Aguateca Sawn Stela |

|

Aguateca is a highly fortified city thanks to its placement on a tall limestone escarpment above the river and is surrounded by deep trenches with few bridges. Takeshi Inomata from Vanderbilt University (above left) heads the current restoration project, but struggles to prevent looters from sawing stela into pieces for sale on the black market. In 2000 the site caretakers were threatened by armed men who destroyed many items, stole others, and deforested the main Plaza of its cedars, mahogany and other trees.

Looters had already removed many monuments from Naranjo by the 1920s, and in the 1960s

they began smashing larger sculptures into pieces to sell. Between 1996 when thieves took

control of the site and 2004 when a conservation project was begun by the

Ministry of Culture and Sport,

the two known looter tunnels had now grown to 270 tunnels and trenches. Listed on the

World Monuments Watch in 2006, hopefully now the presence of workers (their camp, above) excavating and restoring the site as part of the Cultural Triangle Yaxhá-Nakum-Naranjo National Park will put an end to looting.

Sometimes help arrives under the most unusual circumstances. The Mexican government planned to build a dam on the Usumacinta River that would flood part of Piedras Negras, but the team from Brigham Young University and Guatemala's Universidad del Valle couldn’t resume excavations at the site until the Marxist guerrillas from the Guatemalan civil war, who were using the site as a hideout, could be driven out. In 1997, when the 120-man team was finally able to begin work, they discovered that the presence of the guerrilla fighters had actually protected the site from looting.

Not all destruction is laid at the feet of looters or uninformed archaeologist wannabes. In early 2013 a pyramid at Nohmul, the site’s largest structure at more than 60 feet, was bulldozed and used as fill for road construction. Situated on private land, it wasn’t covered by Belizean law protecting archaeological sites. The owners of the construction company were eventually fined $24,000, but the 2,300-year-old pyramid is now gone. Forever.

Sometimes Nature makes the reveal, and other times what Nature has claimed is easiest and best left alone.

A hurricane in the year 2000 uprooted this tree and the cut limestone blocks encased in its roots

in the main plaza of Chau Hiix, revealing pottery shards, stone tools, jade and shell ornaments,

and a plastered plaza floor. One of the last unlooted Maya cities in Belize, it had been kept under wraps

by the Crooked Tree villagers until 1989, when they told a cultural anthropologist about this site.

In the 1990s, the Chau Hiix Project began excavations. As with so many other ancient sites,

it has now suffered major land-clearing by equipment and fire, and in 2013 it was eyed as a

source of road construction material.

A tree embraces a stela in Calakmul’s Grand Plaza, another’s roots hug an altar in Complex R at Tikal, and at Piedras Negras, roots have woven a path through the corner of a building in the West Acropolis. |

Some of the Maya’s accomplishments weren’t taken down by time, Nature or errant explorers. They were deliberate erasures by an intruder who had no understanding or appreciation of these people or their remarkable culture and achievements.

When the Spanish arrived in Mexico, it didn’t take long for them to repurpose many of the existing structures for their churches, homes and roads. Dzibilchaltún was a thriving urban center in the northern Yucatán whose beautiful edifices were torn down for things like the Open Chapel (above left) erected, as a final insult, in the middle of what was the Maya’s Central Plaza. The remains of a 16th-Century Church (above right) at Oxtankah was built atop the rubble of and using stones ripped from that Maya settlement.

Izamal Basilica San Antonio de Padua and Kinich Kak Mo (left); Izamal ruins (right) |

Once one of the tallest pyramids in the Yucatán, Kinich Kak Mo (above left) was so devastatingly destroyed by Franciscan friars for building materials, it is barely visible in the background above today’s Izamál. This image was taken from the Basilica of San Antonio de Padua, which was built in 1553 atop the base of one of the Maya’s main pyramids in contempt of their religious beliefs. Their ceremonial plaza was completely overlaid by the monastery’s main square. Some ancient structures sit in the yards of Izamál residents (above right), hopefully the subject of future excavations.

Thanks to new technology such as LiDAR, GPR, ALSM , 3D scanning, electrical resistivity imaging (ERI) and three-dimensional electrical resistivity tomography (3D ERT), the discoveries keep coming. Even one of the most recognizable structures in Mundo Maya – one that millions of people have admired and climbed in person – had new secrets recently exposed.

Chichen Itza Pyramid Kukulkan

In August 2015, ERI testing revealed the Pyramid of Kukulkán (above) at Chichén Itzá was built above a cenote large enough to hold 4.5 million gallons of water, a sacred natural feature that may have played a part in the pyramid’s location. Two years later, using 3D ERT, a previously unknown 33-foot tall earlier pyramid was found inside Kukulkán, not in the middle of the outer structure but centered over the cenote. Only a few dozen of Chichén Itzá’s structures have been excavated with hundreds more awaiting investigation and possible new surprises.

It’s incredible to realize that many of these ancient Maya cities were unknown to the modern world less than a hundred years ago, and that so many have only been explored within the last few decades. With ongoing work at dozens of sites across Mexico, Guatemala and Belize combined with the hundreds of settlements and thousands of structures that have come to light within the last two years - thanks to LiDAR - archaeologists and scientists and people like me will be entranced for hundreds of years to come.

Other Maya-related articles by Vicki Hoefling Andersen:

Belize: The

Western Frontier

Belize: The

Eastern Edge

Lords of the Petén, Guatemala

Life Along the

Rio La Pasión

Highlands of Guatemala

Palenque, Mexico

Chiapas, Mexico

Abandoned

Cities of Chiapas, Mexico

Ancient Cities

of the Rio Bec

Ancient Cities of the Río Bec

Part 2

Roaming

Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula

Isla Mujeres:

Island of Women

The Maya &

2012: A New Beginning

Discovering the Maya – Part 1

|

|