"It’s very surreal to take away all of the tools we use to keep ourselves resilient - family, sport, church, walking the dog, whatever you use – and see how people cope. Some of my team coped brilliantly while several struggled quite significantly. I think this pandemic has given a great insight into what we experienced, the range and reactions of people are exactly the same as what I encountered with my team." Rachael Robertson

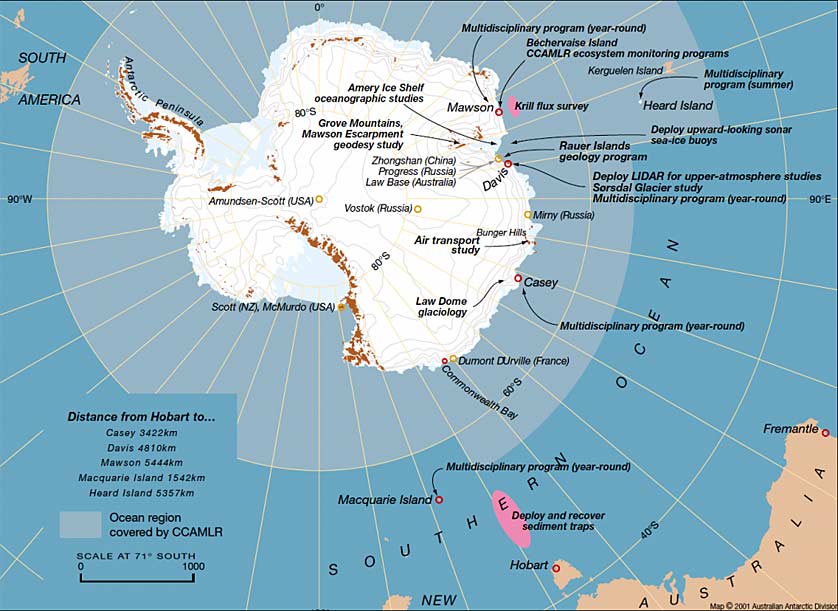

"Cool Science for the Third Millennium" — Australian Antarctic Division —

antarctica.gov.au "Cool Science for the Third Millennium" — Australian Antarctic Division —

antarctica.gov.au

When she was a 16-year-old high-school student in Australia, Rachael Robertson adopted a new motto: "I would rather regret the things I did than regret the things I didn’t do." That changed her life forever and set her on a course of adventure, excitement and challenge.

As a well respected administrator in Parks Victoria, she chanced on a newspaper ad looking for someone to lead an Antarctic expedition for fourteen months. It was a dual-purpose project: A scientific research study, involving more than one hundred scientists during the summer months; and maintainence of the facilities through the long winter with a skeleton crew of eighteen. She decided to give it a go, applied for the position, and after a grueling week of torturous physical and mental challenges with all the other candidates, she was chosen by most of them as best for the job and most likely to succeed in it. Not that other candidates did the hiring, but their support showed the respect that she had earned in merely a week's time. The expedition, which was to be headquartered at Davis Station in the Antarctic, was run by the Australian Antarctic Division. This division hired her. Her selection was such big news in Australia that she was interviewed 38 times the day of the announcement.

| |

|

|

After Robertson was selected for the leadership roll, she and other station leaders were taught specific and unusual things in their three months of training that only they would deal with, such as the grave particulars of acting as station coroner and also their legal obligations under the Crimes Act. They were designated as law enforcement.

On a lighter note, she made a minor discovery in figuring out why Antarctica appeared to have more meteorites than anywhere else. She racked her brain wondering why—was it the magnetic South Pole pulling them in? Was it the size of Antarctica and the fact it was an easy target? Was it the freezing temperatures that somehow left the meteorites in an unbroken state?

None of the above. It’s because snow is white and meteorites are black. So they are easy to see. |

|

| |

Davis Station Leader Rachael Robertson |

|

|

|

About half way through the year, some of the behaviors of the men in particular showed signs of stress and idle brains. The general tendency toward crabbiness and flare-ups toward the end of the year matched what a brain study of a later expedition there reported happens in such isolation and darkness: With so little stimulation - you can't even go outside for four months and it's totally dark for over a month - the executive part of the brain shrinks about 7%. The protein responsible for growing new brain neurons reduces 45% on average. So from about 6 months into their year there, their brains were on a downward sliding scale toward acting like teenagers. Robertson found that she was spending three hours a day on personal issues with her crew.

The over-winter crew of the 58th Australian National Antarctic Expedition

It's now known from a study that after nine months in these circumstances everyone develops the thousand-yard stare, just blank unless something stimulating or distracting happens. The study came years after Roberton's experience, but as she explains below in my interview with her, she was well aware of the symptoms and took measures to mitigate their negative effects. She got together with the station doctor who was sympathetic and together they came up with programs like talk-about-yourself nights, celebrations for anything at all and even parties to mark the passage of time if no other celebratory occasion presented itself.

But as the sun put an end to the constant night, Robertson observed, "It was amazing to see just how quickly the niggly behaviour disappeared with the eternal night. As a unit we went from cabin fever, sluggish, quiet and irritable to high energy and excitement. With the sun came the opportunity to de-ice the equipment, dig out the massive snowdrifts around the station and get back on top of life."

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Magnificant Emperor penguins |

|

Weddell seal pup hours old |

|

Adelie penguin chick |

|

Each chapter of Robertson’s Leading on the Edge has salient wrap-up points like, “Get a mentor!” An example of that, which I read elsewhere, concerned a woman asking a company rep if they offered management internships. The answer was no. She asked if the company would create one for her and the answer was yes. It never hurts to ask.

The book is really about honing leadership skills, which are discussed at the end of each of the 31 chapters, and how the experiences that she had presented big challenges to her leadership. Some examples:

What I learned

"Find a reason to celebrate. When a project has a long lead time, or budget constraints, curtail new projects and it’s

all business as usual. It’s important to find milestones to celebrate. Create them. Celebrating along the way gives a sense of movement and progress, and it builds momentum.

"Take time out. Schedule time away from work and, if needed, away from other people. Rest, reset and restore your energy."

Robertson's survival tips in isolation:

"It's impossible to be spontaneous in Antartica when you have to put on five layers of clothing and a survival backpack just to go for a walk." But she learned to do just that, to go outside and watch the penguins, take pleasure in the colors of the glaciers, any joy she could find that would lodge in her brain.

She teaches that ambiguity is your friend in such situations. There are so many unknowns and changes that no 24-hour time period can be entirely planned out, so learn to go with the flow and avoid frustration if things don't go entirely your way.

Journal daily or nightly, she says. "It's an amazing way to sort your thoughts and put things in perspective." Think of the record of your time, travails, pleasures and successes you'll have when you return to normal life.

Allow no triangles, as in, "He said that she said..." Report directly.

Robertson turned her 2005 experience leading the 58th Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition to Davis Station into a new career of writing and speaking to businesses around the world about the leadership lessons she learned in what she calls "the world's most extreme workplace."

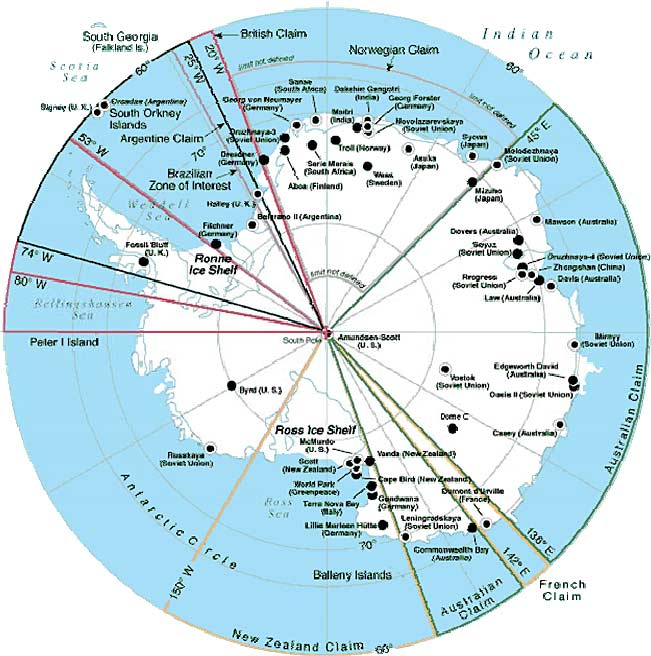

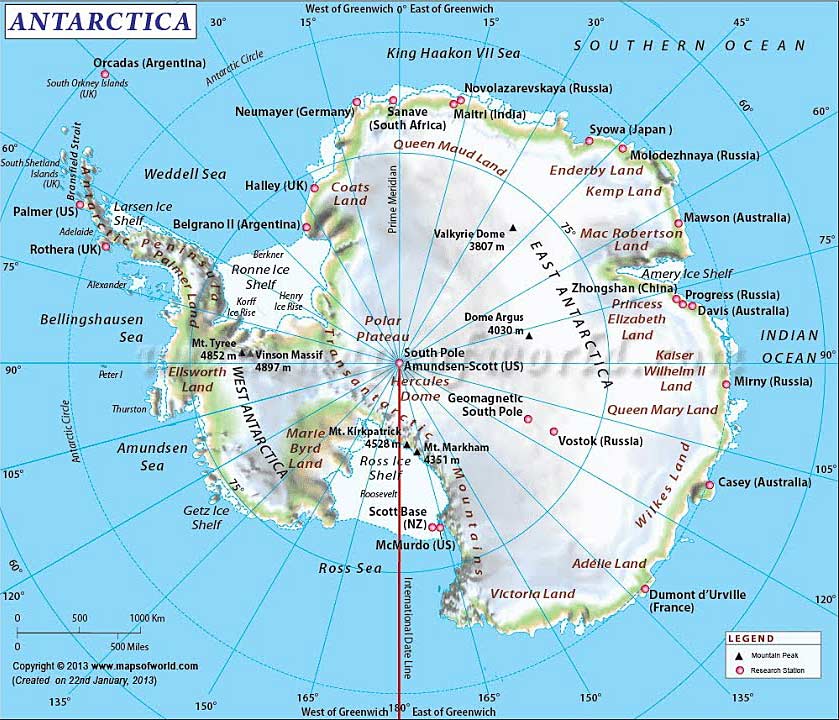

Map of Antarctica showing most stations and pie slice shaped land claims of several nations

Rachael Robertson interview with highonadventure.com in early September of 2020:

Rachel Robertson, (RR), and Steve Giordano, (SG), Q & A

Steve Giordano

Like you said, before this job you were already having a fantastic life, yet you leapt at the challenge of leading a year-long Antarctica expedition and were willing to spend a whole week’s “interview” to get the job. What did you figure the Antarctic experience would do for you?

Rachel Robertson

This opportunity was as surprising as it was amazing. I simply answered an ad in the ‘position vacant’ section of a newspaper. I didn’t know much about Antarctica at the time but I read the job description, then the selection criteria, and I thought I had a chance.

After their selection for centre boot camp, they rang and offered me the job. I decided I’d rather regret what I did, than regret what I didn’t do.

I figured it would be an extraordinary opportunity to visit a place where not many people get to live, to test my leadership skills and to learn a whole lot of new skills. I never expected it to change my life the way it did.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Curious visitor |

|

Icebreaker Aurora Australis |

|

SG

You seem to have an attitude of always saying Yes! to a new experience or challenge, and that the outcome is always positive or at least useful for the future. Where does that come from?

RR

It comes from making mistakes early in my career. I survived them, the sun still came up, life went on. It’s made me realize very few decisions are irreversible. Generally, if I make a decision and I find out later on it was the wrong one, then I make a new decision.

I’m not afraid to admit I was wrong or to learn from other people, which helps too.

I also learned early on to focus only on what I can control or influence. I moved schools a lot as a young girl and I had no control over that. So instead, I focused on how I could adapt to a new school and settle in and make a challenging situation a positive experience.

Davis Station

SG

The brain question: What do you think of the study https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc1904905 that showed a loss of 7% of the hippocampus and a 45% loss of the BCNF that enables & protects new brain neurons, presumably because of the lack of visual and social stimulation over a year’s time in Antarctica? Was it news to you? Did it explain any of the growing problems among the expeditioners? You took constructive steps to counter that effect. Would you suggest more activities now, say like daily aerobic exercise? Zero alcohol, a neurotoxin?

RR

"The biological impacts of wintering in Antarctica are significant. While I hadn’t researched it, and we certainly weren’t briefed on it in our training, I innately noticed subtle changes in people. I didn’t have a name for it, but I would describe it as a general ‘vagueness.’ Some people just didn’t appear as ‘sharp’ as normal, especially during mid-winter. I spoke to our station doctor and together we did some quick research. There was very little known about the impacts but it was certainly documented by previous expeditions. The US Antarctica program called it a “a 20 foot stare in a 10 foot room.

| |

|

|

We took steps to mitigate it, including discussing it with the team – so that we could be kinder, and more accepting, of things like people leaving dirty coffee cups lying around (when they previously hadn’t).

I tried to schedule an activity every night – yoga, movies, snooker competition etc. – to provide an alternative to sitting in the bar drinking alcohol. Not for any moral reason, but rather to keep people busy and active and socially engaged. I was concerned about depression too, so routine became very important to give our days structure. As did celebrating small wins along the way. |

|

| |

Robertson celebrating mid-winter at -13 C |

|

|

|

SG

For me, the scene of the guy building a snow bridge over the diesel line so the penguins could go their usual way was an optimistic sign that you had thoughtful, considerate and talented people on your team. Did that event hold any symbolism for you?

RR

It really did. It showed me I was leading some very proactive and pragmatic people. The team was very solution oriented. I guess that came from the fact that we had minimal choices and we couldn’t call on anyone else for help. So the dominant thinking was “right, what do I need to do here?”

Because there are very few distractions, and we are effectively in lockdown for the year, the wildlife became very important to us and we watched it closely. Not only did it help our mental health to watch the penguins and seals, it also gave us a distraction from each other and the intensity of living 24/7 with work colleagues.

SG

You talk a lot about the values a leader should have and how they could be faked in an interview - you need to see how they perform at work under pressure. You spent the interview week under that sort of pressure, but did you get a chance then or during training to see how the others did? Did you have any say in the team member selection process?

RR

I had absolutely no input into the team selection, which at the time I found very odd. I now know it’s because of the timing. They recruit the expedition team at the same time as the Station Leader so it’s a logistical difficulty to have the leader input to the team selection.

I did start to see personalities coming out in training. We all spent each day off with our various technical specialists, but it was interesting to see which of my team were the social engineers, the ones who would arrange team dinners over the weekend to get the team together. Otherwise we simply didn’t see each other.

We were all staying at the same serviced apartments, so we had to make our own meals and it was interesting to see who would check “do you need anything?” when they went to the grocery store.

I also got to see how people were coping with being separated from their families for the three months of training. Some coped very well, while others seemed to struggle a bit. It was good to have that knowledge before we arrived in Antarctica so I could keep a watchful eye when I needed to.

SG

Your saying “I am such an ‘accidental achiever’ I’m worried I will disappoint. I have never had a life plan, a vision, clarity of purpose. I get through life taking opportunities as they arise.” really resonated with me. Is that still true for you? Is that an attitude than can be taught or fostered?

RR

It is absolutely still true! In fact this pandemic is the first time I have ever sat down and had to plan my career as in 'what will I do now?'

I feel sometimes we place so much pressure on people to have a ‘big life’ – to be bold and creative and achieve great things, when it is perfectly wonderful simply to have a life you enjoy.

I think it can be fostered by building resilience. For me, resilience, in its simplest terms is 'thinking about thinking.'

It’s being conscious of your self-talk and steering, or correcting, the talk into the direction you want. It’s a discipline, and it’s hard, but it can be done. I often ask myself 'what’s the worst that can happen?' and once I’ve done that quick risk assessment I feel confident to make the call.

Two seasons at Davis Station

SG

As the leader under constant scrutiny, did you feel more alone than perhaps the team members did? Like you didn’t feel free to choose your regular meal companions after someone accused you of playing favorites.

RR

It was the hardest part of the entire year, and it’s also why I wouldn’t do it again – as much as I loved the year.

The 24/7 scrutiny was exhausting. All leaders are under scrutiny, and I knew that going in, but I was unprepared for the 24/7 nature of people commenting on what time I woke up on Sundays (our day off) or what I was having for lunch. I believe it was just casual conversation – but the spotlight was on me way more than others.

It meant I had to have incredible self-awareness, and any time I was tired, or home-sick or just not feeling super happy, I had to remove myself and go to my office to reclaim my poise and reign in the emotion. It’s hard, but I couldn’t afford to snap at someone just because I was tired. I was the leader and I needed to lead by example. That’s not to say I didn’t show emotion. I did. But it was appropriate to the event, for example around Easter, when we’d been away from home for six months and many of us were feeling home-sick, I simply said that “I feel a bit homesick at the moment.” That was the truth and it gave permission for others to say that too.

SG

People grouped together like that can devolve into acting like children, which suggests they weren’t self-actualized to begin with. Was there testing for that before the selections were made, or psychological/personality tests to predict how people could handle the life at Davis Station? I’m guessing the scientists qualify on their credentials and grants, but what about the worker bees who seemed more challenging in their behaviors?

RR

You’ve hit on the single biggest challenge for recruitment. The scientists are very difficult to recruit as there are so few in that chosen field. So even if we have concerns about their behavior and ability to live in such difficult conditions, we still need to accept them as they may be the only person available who can operate such technical equipment.

The rest of the team is different as we have a far greater pool of applicants to choose from. We all undergo psych testing – both a written assessment and an interview with an experienced psychologist. The difficulty is that no amount of testing can predict how someone will cope. It might remove the most obvious people who we can see will struggle, but it can’t predict. It’s very surreal to take away all of the tools we use to keep ourselves resilient - family, sport, church, walking the dog, whatever you use – and see how people cope. Some of my team coped brilliantly while several struggled quite significantly. I think this pandemic has given a great insight into what we experienced, the range and reactions of people are exactly the same as what I encountered with my team.

SG

In more recent photos online I’ve seen bicycles being used - were there any during your time there?

RR

We did have a bicycle, but there was really only one road to use it on. That was a road that had been formed with crushed rock and was about ¾ mile long. We couldn’t ride on the ice because of sastrugi – frozen ridges of ice – which act like speed humps. You can’t see them and if you hit them at speed look out!

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Skiway for plains and helicopters |

|

Trekking |

|

SG

Can you teach or mentor that ambiguity is OK? Or just model it?

RR

I tried to teach it. I had a few people on my team who needed perfect information, all of it, 100%. So I had to explain that, at times, we didn’t have all the information, we only had say 80%, and we’d have to work with that. It’s a real challenge for some people – including myself. I don’t like the unknown factors. But that’s just the way it is sometimes, especially in an environment like Antarctica.

One interesting aspect was having an expeditioner who absolutely needed all of the information. He would ask a million questions until he was satisfied with the knowledge. This was interpreted by some of his supervisors as being obstinate or “challenging authority.” So I had to explain to them it wasn’t the case. He wasn’t trying to be difficult, he just needed all the data, it’s the way his brain worked. This cognitive diversity was a huge challenge and it’s where my mantra of “respect trumps harmony” came from.* It makes teamwork a whole lot easier, with much less friction, if we can understand that people think and communicate very differently, and that is perfectly fine and in fact, it’s great.

*Respect Trumps Harmony - Why Being Liked is Overrated and Constructive Conflict Gets Results is Rachael’s book (published 2020) that followed Leading on the Edge (published 2014).

Visit Rachael Robertson at https://www.rachaelrobertson.com.au.

Colorful icebergs

Six Astronaut-Tested Tips for Navigating the Unknown, Overcoming Fear and Surviving a Pandemic

The brain study mentioned above was for the purpose of gathering information that would be helpful for astronauts. The authors figured that Antarctica isolation is the closet situation on earth to isolation in space.

Now, space Flight historian and science writer Amy Shira Teitel, author of FIGHTING FOR SPACE: Two Pilots and Their Historic Battle for Female Spaceflight, distills six astronaut-tested tips inspired by NASA’s history that we can all put into practice right away during our COVID-19 isolation, while we wait for the time we can get back to normal.

1. Prepare Like an Astronaut. Expect challenges. Make peace with uncertainty. Stay informed. Be adaptable.

2. Stay Calm Like an Astronaut. Pay attention to your mental health. Take time for yourself, and even find a new practice to help cultivate a healthy headspace.

3. Sanitize Like an Astronaut. Practice sound hygiene. Wear a mask. Wash your hands. Take precautions to avoid spreading the virus.

4. Stay Connected Like an Astronaut. Stay close with family and friends while social distancing. Take advantage of group chat tools like Zoom. Pick up the phone. Make time to talk and really listen.

5. Stay in the Moment Like an Astronaut. Focus on the positive side of sheltering in place or working from home. Seize an unprecedented opportunity to enjoy your family. Cook meals together. Play games.Turn off the TV. Put down your phone. Set aside time each day to just be present. In retrospect, you just might discover how truly fortunate you are!

6. Look Toward the Future Like an Astronaut. When the world seems bleak and your future feels uncertain, know that there's a light at the end of the tunnel. Trust your instincts, lean on friends and be excited for the day big group gatherings will be safe again.

Visit Amy Shirateitel at www.amyshirateitel.com.

Antarctica map showing the research stations of many nations Antarctica map showing the research stations of many nations

|