| |

In the North Atlantic Ocean, a stone's throw from the Arctic Circle, the 40,000-square-mile island nation of Iceland straddles the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. As the American and Eurasian tectonic plates drift apart, the island is regularly shaken by earthquakes. Geysers and steam vents proliferate, and volcanic eruptions spew ash across the glaciers. Over ten percent of the island lies locked beneath icecaps making it truly a land of fire and ice, and a fitting home to its earliest settlers: the Vikings.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Myrdalsjokull glacier is regularly dusted with ash from Katla, one of Iceland’s largest volcanoes.

|

|

Sitting atop the volcanic “Iceland Plume," the country has become the geothermal capital of the world by putting its endless supply of steam to work heating homes and streets, and fueling power plants. Vents can be seen all alongside any road. |

|

Despite tumultuous geological features, Iceland was an uninhabited land that, to early adventurous explorers, was welcoming with its fertile soil and amazing sights. The first settlement was attempted around 865 CE. Heavy reliance on the bountiful fishing took precedence over procuring feed for their livestock and the animals did not survive the winter. Unfortunately, the group returned to Norway. In 871 CE, an exiled countryman loaded his family, animals and Irish slaves into a pair of ships and set sail for this mythical land to the west.

This time, settlement was successful and a massive land grab ensued. Most of these grabbers were Viking farmers seeking new land. Despite Hollywood’s fanciful portrayal, Vikings did not charge around with horns protruding from their helmets. But they were deservedly infamous for their raiding and plundering when they weren’t tending their farms and eking out survival in a rugged environment.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

An abundance of thermal springs are enjoyed au naturel, much as the Vikings might have done. This hollowed rock spa along the Sculpture and Shore Walk on Reykjavik’s waterfront is blessed with a 100-degree-plus spring source. |

|

Nearby, Sigurdur preserves his abundant catch in much the same manner as his ancestors—he hangs them from the racks in his slat-sided century-old fish drying house so the wind can turn the fish into hardfiskur. |

|

Most Icelanders can trace their family roots to the earliest settlement of the country. Because of its small population, around 325,000, a website and phone app contain entire family trees so folks are able to look up any other Icelander and see how closely they are related. This is certain to avoid much embarrassment in the dating scene.

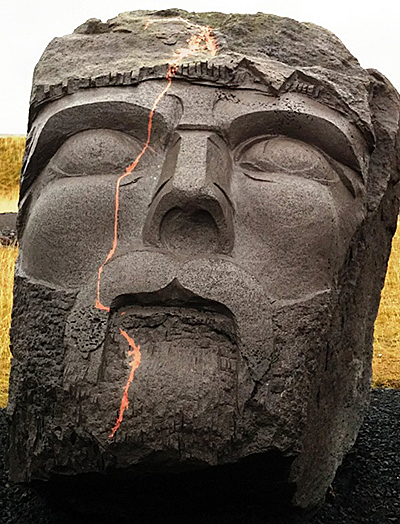

A massive stone Viking head, silent and seemingly lost in thought,

greets visitors to Viking World.

No written records exist from the Viking Age, which lasted from 793 to 1066. But around 1200 CE some Icelandic farmers wrote down their oral history, and these sagas are now some of the oldest tales from western Europe. Deriving their name from the Old Norse verb “segja," meaning “to speak," Icelanders were (and still are) marvelous story tellers. History, genealogy, navigational tips and “news” were shared using poetry and story-telling.

Icelandic is one of the oldest European languages still in use today. Icelanders can read the ancient sagas as easily as we read Old English. New words are discouraged, and if one is needed it is created by an official committee that combines existing words. An example is the word television or “sjonvarp” in Icelandic: sjon for sight and varp for throwing.

Their gift for speaking proved invaluable when it came time to establish some sense of order in a realm with no ruler or overlord. In 930, the Althing was created where local chieftains gathered each summer at Thingvellir, or Parliament Fields, about 30 miles northeast of Reykjavik. Here on the shore of Thingvallavatn, Iceland’s largest natural lake, laws were discussed and disputes were settled. Still assembling today, it is the oldest democratic parliament in continuous existence.

| |

In front of Iceland’s largest church, Hallgrimskirkja, stands a nearly fifty-foot-tall bronze statue of Leif Eriksson, facing west towards North America. It was donated by the United States in 1930 to honor the millennium of the Althing. |

|

|

|

Leif Eriksson, aka Leifur the Lucky, was born in Iceland around 970. About 1000 CE, he led the first known European voyage to the New World. Sorry Columbus, but this is now accepted fact. Leif made numerous expeditions and established a small community. The sagas say he named places he encountered for their most distinctive feature, such as the “Vinland” moniker for an area where wild grapes were found. Early Icelandic maps show “Vinland” situated on the northern tip of Newfoundland, and in 1960 proof was found of a settlement right where the old maps placed it. Viking artifacts were uncovered, the ruins were matched with those from Iceland during that period, and items were carbon dated circa 1000 CE.

The Longhouse, or skali (plural: skalar), was the center of Viking life. A long, narrow wooden frame was completely covered with turf although the walls of some Icelandic skalar were built of stone, perhaps to conserve precious sod. A rock fireplace in the center provided heat, light and a place to cook. Along the walls, ledges served as beds and seating areas on which to conduct everyday tasks. Beneath the streets in downtown Reykjavik, a Viking-age longhouse has been discovered measuring over 65 feet long with a 17-foot hearth.

In 2000, an exact replica of a 9th century Viking ship named Islendingur sailed from Iceland to New York City as part of the millennial celebration honoring Leif Eriksson’s journey to North America. It is now housed at Viking World,

a museum about 30 miles southwest of Reykjavik.

Along Reykjavik’s waterfront, a massive steel sculpture

by Jon Gunnar Arnason appears to be the stylized skeleton

of a Viking ship. In fact, the Sun Voyager

is a dream vessel that pays homage to the sun.

Fast and strong, the Viking longship was amazingly sea worthy and a technological wonder for their day. Shallow-drafted, powered by a single sail and multiple oars, its symmetrical double-end allowed it to quickly reverse direction. The clinker-built design with overlapping planks provided exceptional strength. The longship was a sign of prestige in life and of great spiritual importance after death. A Viking’s ship might be burned and its ashes buried with him; a small ship could mark the Viking's burial; stones placed in the shape of a longship outlining his grave all often served as what we know as tombstones.

Viking burials included tools, weapons, utensils and beautifully fashioned jewelry

This early burial site included parts of a shield, sword and scabbard, axe and spear.

Interred at this Viking's feet,

his trusty horse stood ready to serve him in the afterlife.

Horses were vital to the Vikings and proved critical to survival in Iceland. Originally brought from Norway, today Icelandic horses are one of the oldest and purest breeds in the world. Sure-footed and easy tempered, they handled the harsh environment with aplomb and proved perfect for traveling across lava fields and glaciers, fording rivers, and for use as draft animals and for transporting goods.

To ensure the purity of the Icelandic horse, brought to Iceland

in the 10th century by the Vikings, a 1909 law prohibits the

importation of horses into Iceland.

Two additional gaits make the Icelandic horse unique. The tölt is a four-beat lateral gait with one foot at a time bearing the weight, resulting in a smooth ride. With a fast, two-beat lateral gait, the pace is perfect for speeding across short distances. The sagas are packed with equine tales. One boasts that the Norse god Odin rode a magical 8-legged horse, Sleipnir, who could travel across land, sea and sky. Horses are still used for travel, competition, and the annual sheep round-ups.

Sheep can be found almost everywhere in Iceland except

the glaciers, grazing free until “rettir” or round up in the fall.

Fortunately the Viking longships had plenty of cargo space because not only were horses transported across the northern Atlantic, so were an ancient Nordic breed of short-tailed sheep. Sturdy and resilient, they were able to graze in the winter and provide meat and wool year-round. An important export for the Vikings, Icelandic wool is comprised of two layers: short, delicate fibers surrounded by longer, rough strands, perfect for the creation of warm, lightweight, water-resistant clothing. Today, Icelandic wool sweaters are ubiquitous and a must-have for many visitors.

The “land of fire and ice” epithet should not be a put-off to explore this island country, but rather an enticement to experience the incredible sights, remarkable history, and friendly welcome of her people. There are many places to explore more of Iceland’s Viking history. The National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik showcases 1,200 years of cultural history and includes displays such as the grave items and burials pictured above. Viking World, aka Vikingaheimar, not only houses and tells the story of the ship Islendingur, but presents exhibits about the Vikings of the North Atlantic, Settlement of Iceland, Fate of the Norse Gods, and the Iceland Saga Trails.

In and around Reykjavik are a few places that lean more toward the theatrical than accurately historical. Viking Village (above) is a themed hotel and restaurant a few minutes from the city. At the Saga Museum, dioramas with life-like figures recreate important moments in Iceland’s history. Recreated Viking farms and excavated archaeological sites can be found in various locations across the country.

Note: due to the less-than-familiar Icelandic alphabet, names have been anglicized.

Truffles enjoys watching Icelandic horses grazing pasture land in Fljotshlid.

|

|