| |

An autopolo contest in Regina, Saskatchewan, in 1919 shows

just how dangerous the sport was. (Glenbow Museum Archives NC-38-4)

THERE WAS A time when foxes were catapulted into the air for sport by the German aristocracy; cats were head-butted by medieval Italians; and for a brief time in the early 20th century, personal hot air balloons were worn like jetpacks. Baseball was played with cannon, cheetahs raced against greyhounds, boxers fought on horseback, and Viking challenged Viking to a spot of naked skin-pulling. There is a whole host of wild and weird sports lost to history, but why are they no more? I’ve spent the last few years discovering that the answer to this question is threefold: Cruelty, danger, and ridiculousness.

To study the history of recreation is to study how our society has evolved — from early times in which nearly all entertainment involved treating animals and people terribly, to more eccentric periods in which the concept of calculating risk was merely a coward’s obstacle to adventure. Some of these relics, it could be said, deserve their relegation from currency (donkey boxing and monkey fighting spring to mind), but with others — such as the magnificently silly ski ballet or the spectacular firework boxing — the loss feels like robbery.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

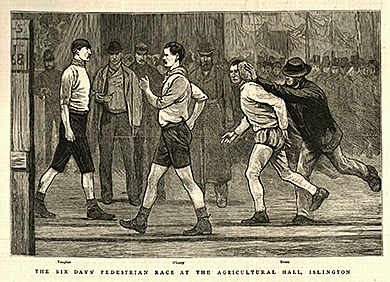

Perhaps surprisingly, there was a decent crowd watching this six-day event at the Agricultural Hall, Islington, as seen in The Graphic, 1878. |

|

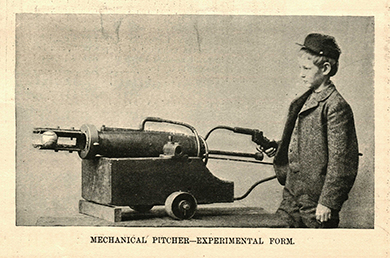

Hinton’s baseball cannon, as illustrated in Harper’s

Weekly, March 20, 1897.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Illustration of Hemming’s “Flying Yankee Velocipede,” taken from J.T. Goddard’s book. |

|

Racing deer in 1935, likely belonging to Maybelle and Wilbur Timm.

|

|

These are both the dead ends and missing links in the evolution of modern entertainment: Out of London’s vicious animal baiting pits emerged modern theater; from auto polo, the demolition derby. The remnants are more subtle, too — did you know that the spiked dog collar originated from wolf-hunting? Or that the term “to beat around the bush” has an ancient and surprisingly bloody origin? Our ancestors amused themselves in shocking, thrilling, and hilarious ways, many of which would be illegal today — but to forget them would be the biggest crime of all.

Battle-ball

Dr. Dudley Sargent of Cambridge was an American trailblazer in the field of physical conditioning, and in 1881 he devised battle-ball, “a game which embraces at once some of the features of bowling, baseball, cricket, football, handball, and tennis.” The rules were numerous, but essentially the teams utilized many tactics to hurl a rubber football past (or through) opponents and across their goal line through baseball-like innings — with no bodily contact.

Ice tennis

| |

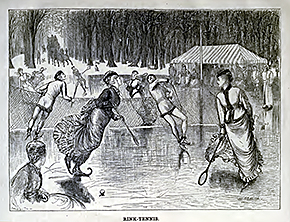

Ice tennis was most popular in New York in 1912 in an effort by local tennis clubs to make their sport as popular in winter as summer. To create the playing area, the clubs simply flooded their outdoor courts and waited for the water to freeze. Advanced skill at both tennis and skating was required if players hoped to survive longer than a few minutes; the ice forgave few errors. The ball also had a tendency to skid rather than bounce on the ice. Doubles matches were the preferred form of play, for it was simply too much for one person to cover the area without the aid of friction. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The Victorian attire shown in this Punch illustration from 1876 was probably not ideal for ice tennis. |

|

Kottobas

| |

|

|

Kottobas was a drinking competition of skill and decadence in ancient Greece, popular in the fourth and fifth centuries BC, in which contestants flung the contents of their wine cups at targets in basins with remarkable accuracy. Maintaining a reclining position at the dining table, the player would deftly flick his chalice with his right hand, sending the remaining wine and sediment flying through the air in one unbroken liquid missile. The game was heavily gambled upon, and because of the element of luck involved, the performance of each contestant was viewed as an omen of future success, especially in affairs of the heart. |

|

| |

A young man is shown playing kottabos on a kylix (drinking cup) from 480-460 BC, discovered in Chiusi, Italy. (Marie-Lan Nguyen) |

|

|

|

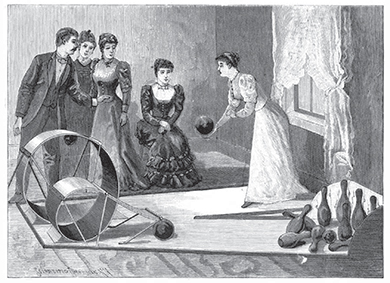

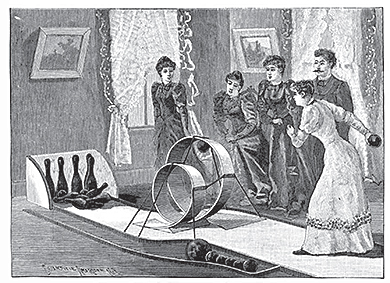

Centrifugal bowling

Centrifugal bowling was simple way to bring the joys of tenpin bowling into the home, as seen in this illustration from Scientific American, May 12, 1894.

In 1885, a proprietor of a Berlin saloon wanted to build a bowling alley. Faced with a lack of space, he engaged an engineer named Kiebitz to solve the problem. Kiebitz visited the site and ordered a drink to mull the issue. By the time he drained his glass, he had conceived an ingenious solution: If the alley wouldn’t fit in the room, he would bend it until it would. The result was a U-shaped, or centrifugal, bowling alley, built with the outer side tilted upwards like the track of a velodrome. An alternative design was introduced in the United States in 1894, which involved an alley shaped in a loop-the-loop design, allowing it to fit in the average residence of the time.

Dwile flonking

In mid-1960s Norfolk, England, it became a favorite activity of locals to gather in a large group, dance to an accordion, and hit one another in the face with beer-soaked rags. The sport was known as dwile flonking and, while chaotic, possessed its own set of rules. Two teams of 12 players dressed in costumes that consisted of a porkpie hat, a collarless shirt, trousers tied at the knee, hobnail boots, and a straw or clay pipe (smoking optional). A “dull-witted person” was selected to act as referee, or “jobanowl,” and a sugar beet was tossed to decide which team should start. The game would begin when the jobanowl cried, “Here y’go t’gither!” The trophy was ultimately awarded to the most visibly unsteady victors.

Flyting

Flytings were extemporary swearing matches that placed a value on the imagination and verbal dexterity of contestants, who would exchange insults with impressive wordplay similar to modern rap battles, but with an intensity of vitriol and florid vocabulary. Flytings can be found in Old Norse and Anglo-Saxon literature as far back as “Beowulf,” but in medieval Scotland is where it was most relished. “The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy,” of 1503, in which insults fly with breathtaking vileness, is considered one of the most famous examples.

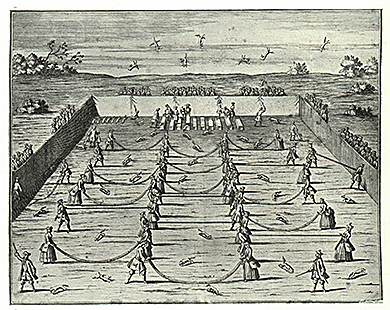

People tossing

The game of throwing someone into the air with a blanket has had a rather strange evolution. In living memory, it serves as a way of celebrating the birthday of the person being tossed; in the 18th century, it was a form of penalty; and in the 16th century, it was an entertainment with a nastier element. The person to be thrown lay down on a broad sheet, the edges gripped by a large group of men, typically 16 in number. Onto the sheet was then poured a sackful of heavy, blunt objects such as work tools, logs, and stones. Then the tossing began.

Friedrich von Fleming shows how fox tossing was deemed to be a sport for couples to enjoy together.

Edward Brooke-Hitching is an award-winning documentary director. His book, “Fox Tossing,” was published in November.

|

|